Huffington Post– What has been the root of the U.S’. inability to develop a sustainable policy or strategy on Iran for the last 30 years? What was not learnt from the Shah’s fall in 1979 and the nature of the revolutionaries who hijacked a pro-democracy freedom movement? And what are the parallels between the Shah’s regime and the current Islamic government in Tehran?

Huffington Post– What has been the root of the U.S’. inability to develop a sustainable policy or strategy on Iran for the last 30 years? What was not learnt from the Shah’s fall in 1979 and the nature of the revolutionaries who hijacked a pro-democracy freedom movement? And what are the parallels between the Shah’s regime and the current Islamic government in Tehran?

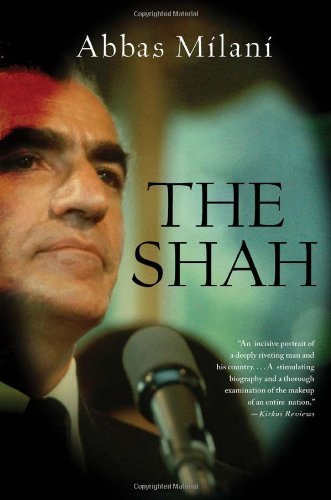

These are the types of questions that have been raised in my extensive interview with Dr. Abbas Milani, author of the recent book, The Shah, and the Director of Iranian Studies at Stanford University in California.

While the Iranian government continues to curb social and political freedom in Iran, particularly after the post-presidential unrests which resulted in killing of dozens and arresting thousands of people, the author of a recent book, The Shah, provides a comprehensive image of parallels that contributed to the fall of the Shah and is now being perpetuated by the Islamists in Tehran.

“If we understand why the Shah of Iran fell in 1979, we can understand why the Iranian government is unstable today and based on that, predict what the future of the country could be”, Milani told me on the significance of reading The Shah.

The book, which is based on more than 400 interviews and newly-released documents by the American and British embassies, also gives very interesting, first hand information and documented accounts of the way the Shah really was and how we should look at him and Iran’s politics today. The 1953 coup and the forces that contributed to such a significant political incident, a view of US-Iran relations and the failure of US intelligence to read Iran’s politics are also discussed in the interview.

Abbas Milani is also the author of a number of books including Eminent Persians: Men and Women Who Made Modern Iran, 1941-1979, (2008); Lost Wisdom: Rethinking Persian Modernity in Iran, (2004); The Persian Sphinx: Amir Abbas Hoveyda and the Riddle of the Iranian Revolution (Mage, 2000); and Tales of Two Cities: A Persian Memoir (1996).

***

Memarian: Why is learning about the Shah still important three decades after the creation of the Islamic Republic?

Milani: Well, I think for two reasons. One is historic in the sense that he is a very pivotal figure of the twentieth century. There is also room for an impartial biography of him now, based on documents that have only become available the last few months.

Politically, I think this is necessary, because in my view the same dynamic, both in terms of the coalition of forces and in terms of political demand, that overthrew the Shah in 1979, have been the cause of more or less incessant unrest and instability in the Islamic Republic in the last 30 years. That coalition wants democracy, and the usurping clerical establishment essentially aborted demand for democracy and the same coalition continues its, now 100-year-old, dream of democracy. So, if we understand why the Shah fell, we understand why the regime is unstable today and I think we can, based on that, predict what the future of Iran will be; that the current status quo is untenable because it’s going against the grain of what the people have empirically shown they want.

Memarian: So what do we learn from your book that has not already been told or revealed?

Milani: My hope is that in different moments of the Shah’s life, I have been able to find new information. If you mean what about the last few months [before the revolution], I can tell you what I think is new about the last few months, but there are also things about his life in general from his childhood.

For example, I have found more or less 150 pages of his childhood or his youthful writing, when he was in high school that no one has ever even pointed to, no one has ever known they’ve existed. I found them in his high school papers and they really reveal a different Shah. They are the youthful writings of the Prince as he really felt and he clearly felt very happy. It was a very joyous period of his life and this later mythology that was created that Switzerland was very bitter for him stands in complete contrast to what he wrote then and what anybody who saw him at the period wrote. They all said he was really very happy there. He was the happiest they had seen him, even his twin sister. That, for example, is about his youth.

The general view about his first ten years in power has been that before [Mohammad] Mossadeq, the Shah was resigned to his constitutional role, and that later, he wanted to participate in politics again. The book demonstrates that is absolutely not true, that he was very much involved, and that he was very much, very soon, trying to regain as much of his father’s power as he could. Because he believed that that’s the only way you can make progress.

And also the coup story, the story of August 1953; again the book shows that the common perceptions is very misguided. The notion that Kim Roosevelt went to Iran with a million dollars and successfully overthrew Mossadeqists is just hard to take very seriously.

The book shows how the Shah’s views of Mossadeq are complicated; the Shah has claimed that he was always a supporter of the nationalist movement. The book shows that this is not true, and that his support for that nationalization was at best tentative, at least in terms of what he has told the British and American embassies.

Memarian: How much was the Shah in favor of instigating a coup against Mosaddeq?

Milani: He was very much opposed to Mossadeq, also, based on documents, that he was not willing to participate in the coup and he only agreed to work for deposing Mossadeq when he thought that he was acting within the Constitution. I have found a letter from Mossadeq that, again, I haven’t seen this being referred to before, where Mossadeq himself confirms in the letter to the Shah that the Shah does have the right to make recess appointment and that’s exactly what the Shah did.

Mossadeq dissolved the Majlis [or Parliament] and only after this, did the Shah issue the farman [decree] to dismiss him and appointed [General Fazlollah]Zahedi.

I have found some fascinating documents about he Shah’s wealth in the mid-to- late 1950’s. The British and American embassies together created a commission and came up with what they thought was the Shah’s net worth, which was a hundred, almost 160 million dollars at the time. I discovered some very interesting stuff about the Shah’s relationship with the Kennedys, and have written almost two full paragraphs about that. Finally, on the eve of the revolution, the last few months of the revolution, I have, for example, some documents to which nobody has had access.

The family of Dr. [Gholam Hussein] Sadighi, the Minister of Interior at the time] kindly gave me access to them. They show the details of how Sadighi was willing to form a cabinet [and] how close he was to forming a cabinet. And it was the Shah who basically decided to not go along, because by then, the Shah had decided that he was going to leave the country because he thought that the Americans wanted him to leave the country.

But in reality, again the documents are very clear; there was no one American policy. The [Jimmy] Carter administration was dismally divided into factions. [The National Security Advisor to President Carter] Zbigniew Brzezinski wanted the Shah to stay through the use of the military if need be, and ban the state department people who basically did not want the Shah. The Shah, who was sick by then, was taking medications that made him more paranoid and indecisive than he normally was. He was, by nature, both depressed and indecisive, but the medication made him doubly so, and that combination, the indecision, the confusion in the White House and in the American policy, the Shah’s belief in conspiracy theories, and his innate indecision and melancholy combined to create the perfect conditions for the revolution that happened.

Memarian: How about his relation with his opponents and allies inside the country?

Milani: The Shah had a completely misguided understanding of who his foes and his friends were. He thought that the left and nationalists were his enemies and he thought the religious forces, minus the radicals of course, were his allies. He went after the radicals, and allowed the creation and in fact the enhancement of the incredible network of mosques, hosseineh’s [religious gathering places], and Quran readings programs throughout the country.

I found some remarkable statistics on the number of mosques, for example, that were built in the last decade of the Shah, and when you compare that to Reza Shah, [the Shah’s father], who literally cut to a third the number of mosques, and to about a third the number of Talabe’s [students of seminaries] you see that the Shah had a scorched earth policy against the left and against the center and he allowed the clergy to organize, mobilize, train their Cal Grads, have their schools, collect their funds and when the system went into crisis, that force was the only force that could keep the country together and the Europeans and the Americans decided that they should make peace with [Ayatollah]Khomeini, [the founder of the Islamic Republic].

The book shows very clearly that Khomeini volunteered contacts with the Americans, he answered their questions; and he advised his allies in Iran to negotiate with the American Embassy. So, in almost all of these phases, the reality, at least as far as I have uncovered, is very, very different than what has been, so far, assumed about it.

Memarian: You said that the Shah essentially was not in favor of the coup in 1953 and did not accept to use excessive force prior to the 1979 revolution, even though a faction in the U.S. was in favor of this policy. What does this say about the Shah to the world? How does this affect the image of the Shah?

Milani: These are two different questions, let me just make one comment on the second part: what I said was that once the Shah decided that the Americans wanted him to leave. But from late September or early October 1978, it was unambiguously the dominant policy of U.S. and Britain to tell the Shah he could not and should not use the military to stay in power. So the Shah was essentially told that he could not count on the military, he should not use the military, even if he wanted, and on a couple of occasions he tried to see weather he could get the Americans and the British to support him. He decided they were not going to support him, because [William] Sullivan, [the U.S. Ambassador to Tehran] was following a policy that was almost completely on his own. Sullivan was not following the White House. Sullivan was the American Ambassador, but he was not following the state department. He was following something like his own foreign policy. Carter’s new memoir makes it clear that they almost fired him because he was acting so irrationally.

But on the whole, I think you are absolutely right, that the Shah was generally adverse to the use of too much force. Even in 1963, he was hesitant in putting down Khomeini’s supporters. It was [Assadollah] Alam who took over the military, who asked the Shah to give him temporary control and basically ordered a crackdown. So, I think if people read the book, the image that they will take away from the Shah is that although he talked tough, although he sometimes talked like an authoritarian despot, he really didn’t have the psychological makeup of an authoritarian despot. He couldn’t make hard decisions, he couldn’t give the order to fire on people and send thousands to their death the way for example the [current] regime today makes this decision.

Memarian: How is it different than the current government in Tehran in dealing with peaceful protests?

Milani: If you look at the number of people killed as a result of assassinations, or through execution by the Shah’s regime, the total number is less that 1,500 during his 37-year rule. Ayatollah Khomeini ordered the death of 4,000 people in prison, in a few months in 1988.

Memarian: Regarding your facts and understanding on the Coup, how can we draw a line between the reality and the myth about the Coup, which has occupied the historical memory of a nation?

Memarian: What I would hope people would take away from it, is that as a nation we have to stop believing in these mythologies. We have to start looking at the evidence and the reality and come to a nuanced judgment. The royalists want us to believe that this is a national uprising, that the 28th of Mordad was a national uprising and that nobody had anything to do with it other than the military and the people of Iran, who rose up against Mossadeq. I think that’s false. The Mossadeqists want us to believe that this was a CIA coup or a CIA-British coup and there was nothing wrong with any of the Mossadeq policies. They want us to believe that the only reason Mossadeq fell was because of the CIA intervention, and had the CIA not intervened, Iran would be a democratic heaven today. I think that’s false as well.

I think the evidence clearly shows that that’s not the case. The evidence shows that the Americans didn’t want to engage in a coup for years, at least for two years. They tried to mediate between Mossadeq and the British. They stopped the British from the use of military against Mossadeq when the British were ready to send in their marines to take over Abadan.

And they resisted, hoping that they would find a negotiated solution. As they waited, Mossadeq’s popularity began to fall within Iran. Mossadeq began to lose his supporters.

Most important of all, he began to lose his support of the clergy. When he lost the support of the people, he lost the clergy, he lost some of his National Front allies, he lost some of the nationalist, like different factions within the coalition that was supporting him and he became more and more reliant on the Tudeh [Communist] Party. When the Tudeh Party became more and more aggressive in its policies, the New York Times reported at the time, the day Mossadeq’s return to power was celebrated on 30 Tir (July 21), where in the morning Mossadegh organized his allies, there were no more than 10,000 people.

In the afternoon, the Tudeh Party brought out 100,000 people; the Americans got very worried that Mossadeq had lost his base and could not withstand the Tudeh Party. It’s that combination, and constitutionally, it is the referendum that I think made the issuelegally more complicated.

There is a long history of recess appointments by the Shah when there were no matches left.

[The Interior Minister, Hossein] Sadeghi told Mossadeq, ‘you are a Constitutionalist; you should know that the Constitution, that the Shah, will have the power to dismiss you, if he dismissed the Parliament. Don’t do this referendum. First of all this referendum is a dubious constitutionality itself. And second, if you do the referendum and win it, you will open the legal possibility for the Shah to dismiss you.’ Mossadeq said: ‘he won’t dare.’ Well, he did dare. And he dared because again the Americans, of course, pressured him, the British pressured him, the clergy sent him a message, saying that that they were now with him and the rest, of course, we know.

Memarian: What kind of dynamics led to the resignation of Mosaddeq and initiating a coup?

Milani: Almost immediately after Mossadeq came to power, Ann Lambton, the most influential British advisor, told the foreign office: ‘you’re not going to get anywhere with Mossadeq. I know him. You should try to organize a coup and topple him.’ The British Embassy immediately contacted the Shah and told him to ‘dismiss the Majlis and dismiss Mossadeq and appoint someone else.’ The Shah said ‘no I won’t do it, this is not constitutional. I want to get rid of Mossadeq. I don’t believe that his policies are good for the country. I don’t believe that nationalization, the way he wants it, is good for the country, but I won’t simply dismiss him. There is no constitutional basis for this. I have to go convince the Majlis to give him a vote of no confidence, and then, if they give him a vote of no confidence, I will dismiss Mosadeq and the British couldn’t get the votes.’ And consequently they do it.

On 30 of Tir(21 July) , Mossadegh says to him, ‘I want the power to run the military.’ The Shah says, ‘I am Commander-in-Chief’ and he is, the Shah is the Commander-in-Chief, although there were different interpretations of what Commander-in-Chief meant, but the Shah understood it to mean that he really controls every facet of the military. Mossadeq wanted to control the military, the Shah said ‘no,’ and Mossadeq said ‘I will resign.’ And he did resign. The Shah said ok, I would accept your resignation. He surprised Mossadeq. Many of Mossadeq’s allies criticized him at the time saying ‘why did you do that?’ and then people began to rise up against [Prime Minister Ahmad]Ghavam. For five days there was increasing violence against Ghavam. Now because the Shah did not like Ghavam, the Shah did not allow Ghavam to use the military to put down anti-government demonstrations.

That’s why the British Embassy, for example, believed that the Shah wanted Ghavam to fail. So on 30 Tir, all of these factors worked hand-in-hand and allowed for the return of Mossadeq. And when Mossadeq came back, he was much more powerful. But still, the Shah resisted the idea of a military coup against him, or of outright dismissing Mossadegh. He wanted to find a constitutional way of doing it.

Unfortunately, our national debate on this has become reduced to, and to some extent the American discussion about this, an either/or polarized choice. Was it a CIA coup or was it a national uprising? My suggestion in the book is that it was neither. It was a process. It was a long complicated process, the result of which was determined by a large number of factors. One of those factors, clearly, was the fact that the CIA was trying to topple Mossadeq– the CIA from November 1952, and the British from the moment Mossadeq came to power.

That was certainly a factor, but it was not, in my view, the only factor, and it was not even the determining factor. The determining factor was the domestic situation in Iran. It was some of Mossadeq’s errors that created the conditions that gave rise to, what we now call the August ’53 situations.

Memarian: The Royal family did not accept to be interviewed for the book. How your book would have been different if they decided to do so?

Milani: Well, I think it would be a different book, certainly. There were two members of the royal family that I was particularly interested in interviewing and I made repeated efforts to do it. One was the Shah’s twin sister Ashraf, and the other one was the Queen. The reason was that there are issues, there are moments in the Shah’s life that only these people would know the details of. I can find the documentary trace for them, but they could have provided the emotional context for those decisions. So, they decided not to do it. I think it damaged their opportunity to have their story told, because my guess is, that if the last book on [Amir Abbas] Hoveyda is any measure, this book will have a lot of readers. This book could have been a good opportunity to set the record straight or at least give their version of the events in a context that is not a self-serving context, like a memoir or like a biography written by someone who is close to the royal family or is a member of the royal family.

Memarian: In writing the book did you find any parallels between the Shah’s time and the ruling of the ayatollahs in Iran now?

Milani : Absolutely! I think that there are so many parallels. For example, if you look at the documents and American, British, and CIA reports, you see that between 1975 and 1978, three years before the revolution, almost universally, and I say almost because there are some dissenting views, the view of the Americans and the British is that the Shah is here to stay, the opposition is completely demoralized, everyone is only thinking about their own interests, the Savak is in full control, and the military is unbeatable.

In a study that the British commissioned right after the fall of the Shah, they tried to understand why they had been so wrong. The study is called British policy in Iran and was written by someone named M.W. Brown and is now available online, almost 97 pages. The person who had access to all of their files, said they underestimated the brutality and thus the flight of the secret police, they did not understand the public perception and resentment of corruption amongst the ruling elite. And they did not understand the power, the pervasive power, of the opposition.

I think this could be almost exactly a recipe for what is wrong with some of western thinking about Iran today. They don’t understand how fed-up people are with this regime; they don’t understand how corrupt this regime is. And they don’t understand how brutal the political structure of this regime and the military and [the Revolutionary Guards] IRGC and the intelligence Ministry is and thus they are missing the boat.

The other parallel is between [the Supreme Leader, [Seyyed Ali] Khamenei and the Shah. When problems began to arise, early on, the Shah did not believe they had internal domestic resources. The Shah believed that the CIA, the British, communists, oil companies, or all of them, at one time or another, gave resources to the culprits. They were the guilty ones who were making this revolution, he thought. So, instead of addressing the domestic problems of discontent in the country, he kept trying to solve his problems by accusing these different sources, or trying to silence the BBC or the Western media, never understanding that the problem was that he, himself had created a middle class, an educated class, a working class, that expected more of life, that wanted a share in the political structure.

So, instead of addressing that issue, he kept trying to solve the conspiracy that he thought was against him.

Khamenei has made the exact same analysis. When 3 million people came out in the streets, his instinct was not to say ‘well I’ve made some major mistakes, [and that] there are millions who are opposed to me and are risking life and limb in order to say ‘death to the dictator.’ Instead, he decided to kill the messenger. He deiced to accuse the Western media, he decided to accuse you and me and Yale and other universities of instigating this. This is exactly what the Shah initially did.

And by the time he tried to address the domestic situation, it was too little, too late. I absolutely believe, though I can’t prove this–its’ just my sense after having read all that I have–that if the Shah had made a third of the concessions that he made in 1978 under duress 2 years earlier, when he wasn’t under duress, today we might have been living in a very, very different Iran. There was no inevitability about the clergy coming to power in Iran; there was inevitability about one thing–democracy.

And if the Shah had understood that he could have made Iran a democratic monarchy. And if Khamenei understands that he could have accommodated [Mohammad] Khatami, which was the last hope for this regime’s survival. [Khatami], in my view, was Khamenei’s last chance.

Memarian: In one of the chapters, you extensively explain how the Shah was surrounded by those eyes and ears that did not tell him the truth and/or his obsession to fully arm the country and have access to the latest weapons in the market and that kind of thing. It seems that we are witnessing the same phenomena in Iran now, it’s like Iranians are not interested in learning from their history.

Milani: I think you are absolutely right; there are so many parallels. The other parallel is the one I think you are alluding to, and that is the fact that gradually, as the Shah’s power increased, there were fewer and fewer people who dared tell him the truth. By 1975-1976, the Queen was really the only person that dared tell him the truth and, occasionally, confront him. [Assadollah] Alam was certainly not doing it, and Hoveyda [the Prime Minister] was certainly not doing it. I cite a CIA report, or an American report, that says ‘even foreign diplomats no longer really dare tell the Shah the truth,’ and you know Iran was in possession of so much money that everyone wanted to get a piece of it. So, he surrounded himself with domestic sycophants. And he had no shortage of international sycophants.

I quote Rockefeller who wrote in a letter to the Shah that ‘we wish we could bring the Shah to America and rule here for a couple of years to show us how to run a country.’ When you are surrounded with these kinds of people and then when someone heads your Intelligence Ministry, Savak, like [Colonel Nematollah] Nasiri, who is literally unwilling to take bad news to the Shah, then you have trouble.

I point to something that to me is really remarkable. The Shah had seven top intelligence officers serving him in heading the Savak, or the Deputy Directors of Savak. They were [General Teymour] Bakhtiar, [General Hassan] Pakravan, [General Hassanali] Alavikia, [Colonel Nematollah] Nasiri, [General Hossein] Fardoust [General] Valiollah Gharani, and [General Reza] Moghaddam.

Of the seven, General [Teymour] Bakhtiar was accused of conspiring to overthrow the Shah and was killed by the Savak when he was in cahoots with Iraq. Savak sent a team and the Shah ordered him executed and they killed him in Iraq. I described this in detail in my book.

The second one was General Nematollah Nasiri, killed by the regime, but unwilling to tell the Shah the truth for much of his tenure, insome of the most important periods. For 13 years he was the head of Savak and he was literally pressuring people not to give him bad news.

General Valiollah Gharani, who was head of the Army Intelligence before the Savak was created, and thought he, should be the head of the Savak. He was arrested and accused of organizing a conspiracy against the Shah.

General Hossein Fardoust, Deputy Director of the Savak, was accused of having been critical of the Shah, if not conspiring against him from the beginning.

General Hassan Pakravan was easily the best head of Savak in the sense that he ended torture. He tried to have a rapprochement with the opposition; he tried to create a think tank in Savak that would tell him what was going on with the country. He served the shortest period and the Shah got rid of him almost immediately, because he didn’t like his ways.

General Hassanali Alavikia was accused of being a Teymour Bahktiar co-conspirator, and was retired in 1967. And these were the eyes and ears of the Shah, these were the heads of the Intelligence Ministry. Almost every report you read from the American Embassy or the CIA says ‘Savak is the pillar of the Shah’s power, [but] when you look at this pillar, it’s rotten.

Now we know that from late 1978, General Reza Mogaddam, , the last head of the Savak, was very much negotiating with Khomeini and his allies and was very much instrumental in neutralizing the army in favor of Khomeini. So, you have these leaders and all of them, with the exception of General Alavikia who now lives in the United States and was forced to retire in 1967, either died a violent death, or at least four of them, Bakhtiar, Gharani, Moghaddam, and Fardoust, have been directly accused of organizing conspiracies against the Shah.

Memarian: Just to refer to another parallel that I see in one of the chapters, ‘Cat On A Hot Tin Roof‘, you mention that the Shah or people close to him suggested that the American Embassy should avoid any contacts with dissidents or even opposition elements of the Parliament [or Majlis]. Today, not surprisingly, it’s very costly for the opposition or anybody to be in touch with embassies in Tehran. So how does such paranoia plays out in Iran’s politics and its relationship with the world today?

Milani: Yes, that’s one of the more remarkable cases of double standards. The clergy in the current regime, when they were among the Shah’s opposition, had a great deal of contact with the American Embassy and with other embassies. They solicited contacts, they volunteered for contacts. As I said, Ayatollah Khomeini volunteered to contact Americans in Paris. Now, the mere fact that [Mir Hussein] Mousavi [the opposition leader], for example refers to an American report is claimed by Kayhan [a radical conservative newspaper in Iran] to be once again another proof that he is an agent of the CIA.

First of all, the hypocrisy is remarkable! Second of all, you are absolutely right. The Shah began pressuring both the Americans and the British to stop their contacts with the opposition. And eventually, he didn’t get it in 1959 because he wasn’t in a position of power but by 1965 he got it. By 1965, both the Americans and the British stopped contacts with the opposition inside Iran.

The result was that they failed to understand what was going on in the country. They failed to understand the level of deep-seated resentment in the country and as a result, by the time they found out that something was wrong, something was rotten in the state of Denmark, as Hamlet would say! By the time they found this out, it was far too late. There was nothing they could do. And as a result of the Shah’s paranoia and belief in conspiracy theories, he would not even tolerate the American Embassy’s inviting Ali Amini, the Prime Minister of the country, someone who had previously been the Secretary of the Treasury, and who had been Iran’s Ambassador to the US, to be invited to a dinner at the American Ambassador’s residence. He threw the equivalent of a diplomatic tantrum when this happened.

So, this kind of lack of contact simply made these countries unaware of what was going on in the country, and it made whatever contact there was to be even more illegal, more underground and ultimately more limited, and the result, I think, that was disastrous for both the western powers and for Iran.

Knowing about the opposition and what is happening in the country can be a source of information for the regime. In other words the Ambassador might learn it and he might, in the next meeting with the Shah, for example, tell him ‘look, this is what we are hearing and these things are happening.’ We see this, in the 1950’s, when the opposition is having contact. We see, for example, some opposition figures talking to the Ambassador and a few days later, the Ambassador writes a report to the State Department, the State Department writes back to the ambassador, saying that next time you see the Shah, tell him this and this and this, which essentially means tell the Shah that this is what the opposition is saying and even if the Savak was not doing what it was supposed to be doing, the embassies might have been able to do it.

But now this regime has a siege mentality and thinks that the whole world is against it and it thinks that by cutting off contacts inside Iran, it can save itself from the wrath of the people. It only adds to the complexity and the direness of the situation.

Memarian: It seems that the U.S. government simply suffers from a sort of severe disconnection disease in order to lay out a long term strategy in dealing with Iran. How might this lack of connection and, even misinformation they could receive from second hand sources, contribute to a series of miscalculations, misunderstandings, and unrealistic policies?

Milani: I think part of the problem of the U.S. policy in Iran or the U.S.’ inability to develop a policy on Iran that has any sustainability is that if you look at it, the US really has not had a strategy on Iran for 30 years. They’ve gone from one reaction to another. A kind of a strategic vision that is based on a concrete realistic intimate understanding of the situation has been wanting. And one of the reasons it is lacking, and it’s difficult to make, is that they have no embassy.

When you have no embassy, when you have no diplomats telling you what is happening on the ground, when you don’t have intelligence agencies doing exactly what intelligence agencies are supposed to do, which is report about the realities on the ground, and then you can’t come to a good assessment.

…When you don’t have an embassy, you become reliant on a phone bank in Istanbul calling 700 people inside Iran, 702 to be exact, and asking them what their opinions are on very sensitive issues. And to think that you could possibly get a correct answer from a call from Turkey to an Iranian living under the current oppression in Iran is a level of desperation that is hard to fathom. It shows a desperate need for information. It shows a level of desperation in accessing information that is truly remarkable; hard to fathom, hard to understand.

Excerpts of this interview were published by IPS News Agency, and reprinted by Lebanon’s Daily Star.