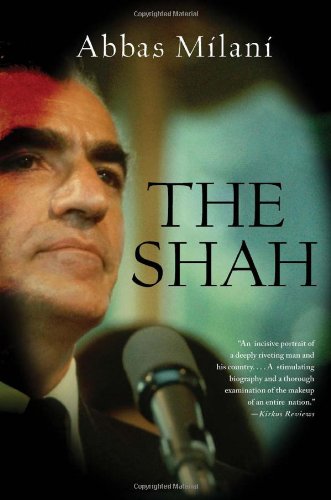

SAN FRANCISCO, California, Jan 17, 2011 (IPS) – In “The Shah”, a prominent Iranian author and scholar at Stanford University in the United States offers new insights into Iran’s modern history, including the 1953 coup, the revolution a quarter century later, and the current repressive political situation.

“If you understand why the shah of Iran fell in 1979, we understand why the Iranian government is unstable today and based on that, predict what the future of the country will be,” Abbas Milani told IPS.

Drawing on more than 400 interviews and newly released documents by the U.S. and British embassies, “The Shah” traces the rise and fall of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, who died less than a year after his ouster.He is remembered for efforts to modernise Iran’s culture and economy, including giving women the right to vote, but also for the lack of freedom of speech and assembly under his regime, and severe political repression.

Excerpts from the interview follow.

Q: Why is learning about the Shah important three decades after the Islamic Revolution in Iran?

A: For two reasons. One is historic in the sense that he is a very pivotal figure of the 20th century and I think there is room for an impartial biography of him based on documents that have only become available recently.

Second, because in my view the same dynamic both in terms of the coalition of forces and in terms of political demands that overthrew the shah in ’79 has been the cause of more or less incessant unrest and instability in the Islamic Republic in the last 30 years.

That coalition demanded democracy and was essentially aborted by the usurping clerical establishment.

Q: What can we learn from your book that has not been already revealed?

A: [That] the Shah had a completely misguided understanding of who his foes and his enemies were. I found some remarkable statistics on the number of mosques, for example, that were built in the last decade of the Shah. When you compare that to Reza Shah [the Shah’s father] who literally cut to a third the number of mosques, and to about a third the number of talabes [students in seminaries], you see that you have a scorched earth policy against the left and against the centre and you allow the clergy to organise, mobilise, train, have their schools, collect their funds and when the system went into crisis, that force was the only force that could keep the country together.

And the Europeans and the Americans decided that they should make peace with [Ayatollah] Khomeini [the founder of the Islamic Republic], and again I have shown very clearly that Khomeini volunteered contacts with the Americans, he answered their questions, he advised his allies in Iran to negotiate with the American embassy. So in almost all of these phases the reality, at least as far as I have uncovered, is very, very different than what has been, so far, assumed about it.

Q: The royal family did not agree to be interviewed for the book. How would it have been different if they had decided to do so?

A: Well, I think it would be a different book certainly. Particularly two members of the royal family that I was very interested in interviewing and I made repeated efforts to do it. One was the Shah’s twin sister, Ashraf, and the other one was the queen.

There are moments in the Shah’s life that only these people know the details of. I can find the documentary traces for them but the emotional context for those decisions could have only been provided by them.

Q: In your book you portray the disconnection of foreign intelligence services from Iranian society and politics, which led to a number of failures in reading Iran’s current political events. Is there any parallel between the revolutionary era and the current moment?

A: The U.S. really has not had a strategy on Iran for 30 years. They’ve gone from one reaction to another. A kind of a strategic vision that is based on a concrete, realistic, intimate understanding of the situation has been wanting.

And one of the reasons it is lacking, and it’s difficult to make is, they have no embassy. And when you have no embassy, you have no diplomats telling you what is happening on the ground. When you don’t have an embassy, you become reliant on a phone bank in Istanbul calling 700 people inside Iran, 702 to be exact, and asking them what their opinions are on very sensitive issues.

And to think that you could possibly get a correct answer from a call from Turkey to an Iranian living under the current oppression in Iran is a level of desperation that is hard to fathom. It shows a desperate need for information.

(END)